Sara Ather

Scores of homes and properties belonging to Indian Muslims were demolished recently in the states of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh, India. The controversy that led to these demolitions began in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, where Muslim residents displayed a banner reading “I Love Muhammad” during Eid Milad un Nabi celebrations, which rapidly escalated into a nationwide crackdown. The display was deemed provocative by local police, leading to arrests under the pretext of disturbing communal harmony. According to news reports, more than 4,000 Muslims were subsequently booked and hundreds arrested across several BJP-ruled states for displaying or chanting the slogan. The state response extended beyond mass FIRs to punitive demolitions of Muslim-owned homes and properties, a phenomenon that has become far too common a punishment for Muslims in India.

The arrests were followed by an address by the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, the state that went through the harshest crackdown. In his address, he proclaimed that “the Maulana has forgotten whose rule he is living under”, referring to the Muslim leaders who were leading protests in solidarity against arrests. The Chief Minister insists(in his address) that religion for Indian Muslims must remain a private affair, that the public space has to be respected as the space of the nation, while the nation is the nation of the majority. However, in its simultaneity, while promising the relaxation of religiosity to be practiced in the confines of one’s home, an open war has been declared on the private existence of Muslims.

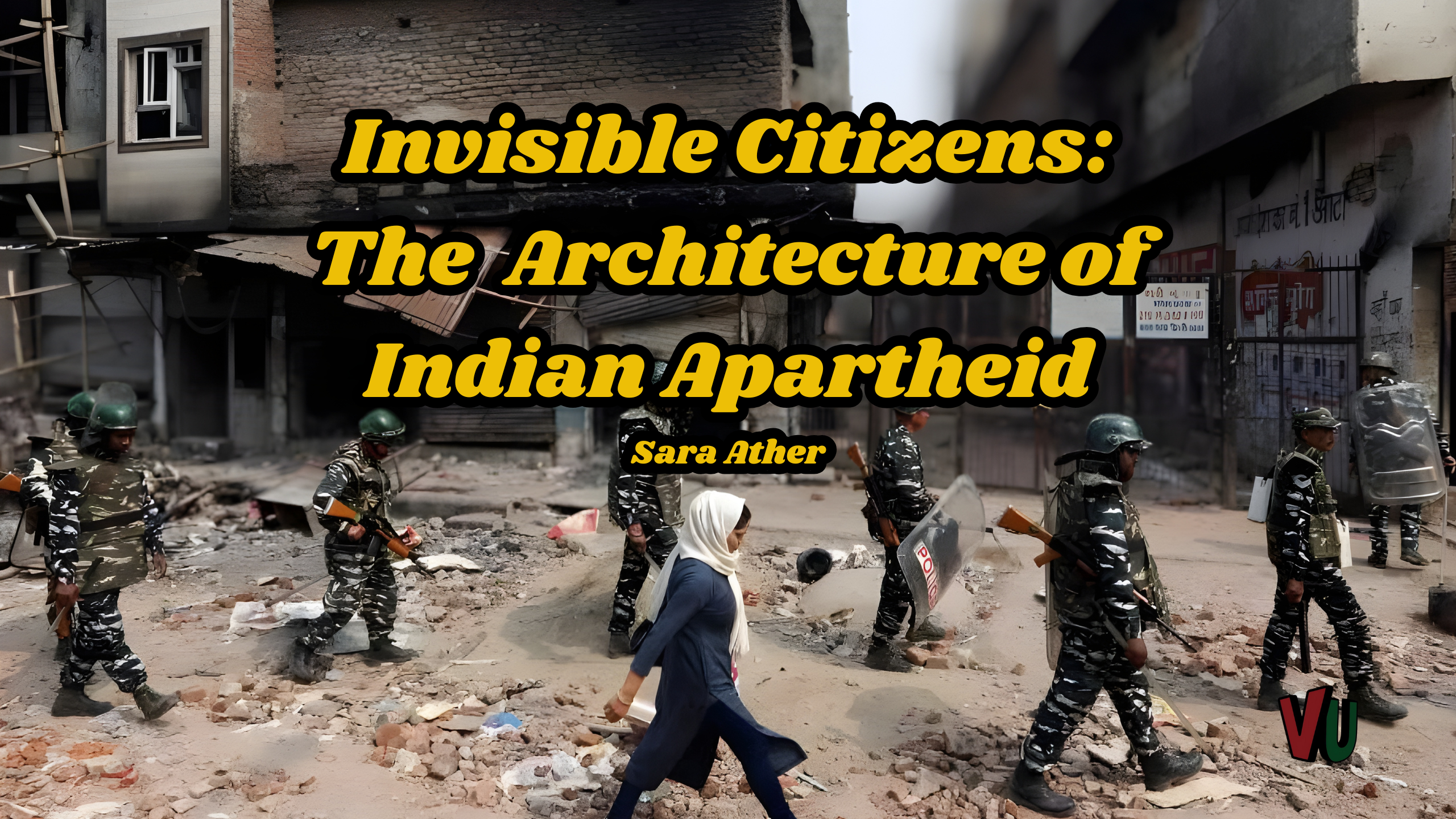

There is an open apartheid emerging in India, against Indian Muslims, enabled not just by widespread Islamophobia, but equally through the direct backing of the government and police forces. Muslims are targeted not only for being visibly Muslim in public spaces but equally within the four walls of their homes. The line between public and private—the supposed boundary of India’s secular promise—has evidently collapsed. The anxieties of the majoritarian regime now dictate what stays and what gets erased from the nation-state.

Akin to Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon who had earned the name of “Bulldozer” for his relentless policy of demolition of Palestinian homes, Yogi Adityanath- the chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, has earned a similar reputation for his demolition policies, and has been given a popular nickname of “Bulldozer Baba” due to his frequent deployment of the JCB by his government to raze properties owned by Muslims in the state. Israel’s position as an ideological ally of Hindu nationalists has further influenced their approach, as the BJP-led government increasingly mirrors Israeli tactics of enforcing apartheid-like conditions against the Muslim population.

However absurd the act of deploying bulldozers against people protesting their right to hold a placard in public might seem, this recent controversy is far from the most egregious instance of home demolition. In recent years, Muslim homes and properties have been razed on the flimsiest of pretexts, including but not limited to suspicion of storing beef in a refrigerator, accusations of engaging in “love jihad” (a right-wing conspiracy theory claiming that Muslim men lure Hindu women into marriage to convert them to Islam), or allegations of pelting stones from their rooftops. Homes of Muslim activists and politicians have been demolished after being scapegoated in cases of public dissent against the government. There have also been targeted demolitions carried out under fabricated charges of “land jihad” (a conspiracy theory asserting that Muslims are systematically encroaching upon state land as part of an alleged demographic expansion). In effect, every conceivable justification has been weaponized by Indian authorities to demolish the built spaces of a people whose past and present the administration seeks to erase.

There have been demolitions of shops owned by Muslims, mosques visited by Muslims, shrines worshipped by Muslims, madrasas occupied by Muslim orphans, as well as agricultural farmlands owned by Muslims. The bulldozer has emerged not just as an instrument of administrative function, but also as a symbol of the dictatorial force that underpins the necropolitical logic of the present-day administration.

While sparing no effort to police the very presence of Muslims in public spaces, Hindu religiosity and processions, on the other hand, have seen an unprecedented public expansion in the past few years. These festive processions not only dominate and redirect the flow of urban life but have also come to symbolize the changing nature of public space itself, a space increasingly defined by two divergent secularisms. In the emerging fascist context of India, secularism no longer functions as a neutral framework; instead, it operates as a selective technology of governance, authorizing which religion’s presence in public space is celebrated as “cultural” and which is condemned as “political.”

Under the BJP administration, every form of shared space that brought together communities of different faiths has suffered a rupture, including shared places of worship, business ties, and the possibility of having inter-religious marriages. The second and third terms of the BJP have also seen multiple campaigns led by Hindu nationalists against Namaz being offered publicly, as well as a growing demand for banning the use of loudspeakers for Azaan. As the popularity of Hindu nationalism has grown among the masses, so has a violent reassertion of monopoly over public spaces.

It has, in fact, become standard practice, particularly in the days leading up to Eid, for authorities to impose severe restrictions on public prayers, sometimes even filing FIRs against Muslims who offer Eid prayers in open spaces. On university campuses, students have been violently attacked by mobs of Hindu nationalists for performing Namaz, even in quiet corners of public areas. And in nearly every case, it is not the attackers who are held accountable, but the students themselves. The institutional response has often been to ban religious practice in public altogether, sending the clear message that Muslim faith and presence must be hidden from view.

These are attempts to not just discriminate against Muslims but rather to establish Muslim cultural expressions as incongruent with the overarching narrative of the Hindu nation. Concurrently, the goal is to completely desynchronise Muslims from the emerging ideal national community of the Hindu homeland. A perceptible schism is being created, a rupture that explicitly signifies: “Your world does not intertwine with ours” ensuring a social death of Indian Muslims.

To be a Muslim in India today is to live a life of constant hypersurveillance of one’s public identity. The denial of public space, both physical and discursive, gradually displaces minority communities not only from the landscape but from the nation’s memory and moral imagination. The trauma of living through this open apartheid is not solely being the subject of violence; it is the constant negotiation to be recognised as traumatised. While the news coverage shows us counts of lynched bodies, counts of bulldozed homes, counts of demolished mosques, the fight back home is a struggle to convince others, and often even to oneself, that this really is a significant number, that we are not suffering because we deserve it.

The site of fascism is not outside in a separate place of the concentration camp; its site is in the quotidian, in the regular everyday life, which is being changed in inconceivable ways. The trauma of living through this apartheid is not seeing an existing fringe turning into a more fanatic version of itself, but seeing your own neighbors turning into informants and supporters of that fringe. It is seeing the most familiar things of everyday life turn into hostile environments without warning. It is precisely in this unpredictability of the danger being nowhere and everywhere at once.

Every time a new act of violence erupts, the earlier trials and older patterns have to be explained. At the same time, the burden of it mostly all falls on a dozen Muslim journalists, a handful of media houses, and a few muslim activists who have to maintain clear maps of connections explaining histories, motives, and ambitions of a well-functioning hate regime to a population of people who forget too soon, who remember too little.

The dangerous predicament India’s 207 million Muslims find themselves in today is a continuation of a more extended history of segregation, ghettoisation, and surveillance culminating in present-day policies of extermination. India is home to the third-largest Muslim population in the world. And yet the scale at which Muslims have been suffering an unprecedented attack on their citizenship in India has barely gained attention in the world.

Muslim activists, including Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, among many others, who have raised their voices against the emerging apartheid model of citizenship in India, have been behind bars for 5 years, without a trial, on flimsy charges, without having their sides heard. The invisibility of the Indian Muslim population in the international community has contributed to the marginalization of their plight, where, despite being home to the third-largest Muslim population in the world, Indian Muslims receive barely any attention from the international community. The world must wake up to the reality of a population that lacks not only visibility today, but equally the presence of any support system within its ecosystem to fight back amid the depleting systems of accountability. The world must turn its eye towards the unfolding of a slow, methodical annihilation of a people, persecuted for nothing other than the history and faith they represent.

Sara Ather is an architect, columnist, and a PhD student of architectural history at Cornell University