Iman Benabdelsadouk

Do not say of those who are killed in the cause of God, “They are dead.” They are alive at their Lord, but you do not perceive [2:154]

The camera is a weapon in the anti-colonial struggle for liberation. It does not just record – it exposes. It bears witness to what the colonizer tries desperately to hide. It shows the slaughter and forces the world to look. For many, the camera is the only witness. The lens sees when we don’t. When we can’t. To take the camera away leaves the narrative in the hands of the colonizer.

If the camera weren’t dangerous, why are those who wield it killed, exiled, or bought off? The camera is costly to the colonizer, but what if it’s also costly to the victim?

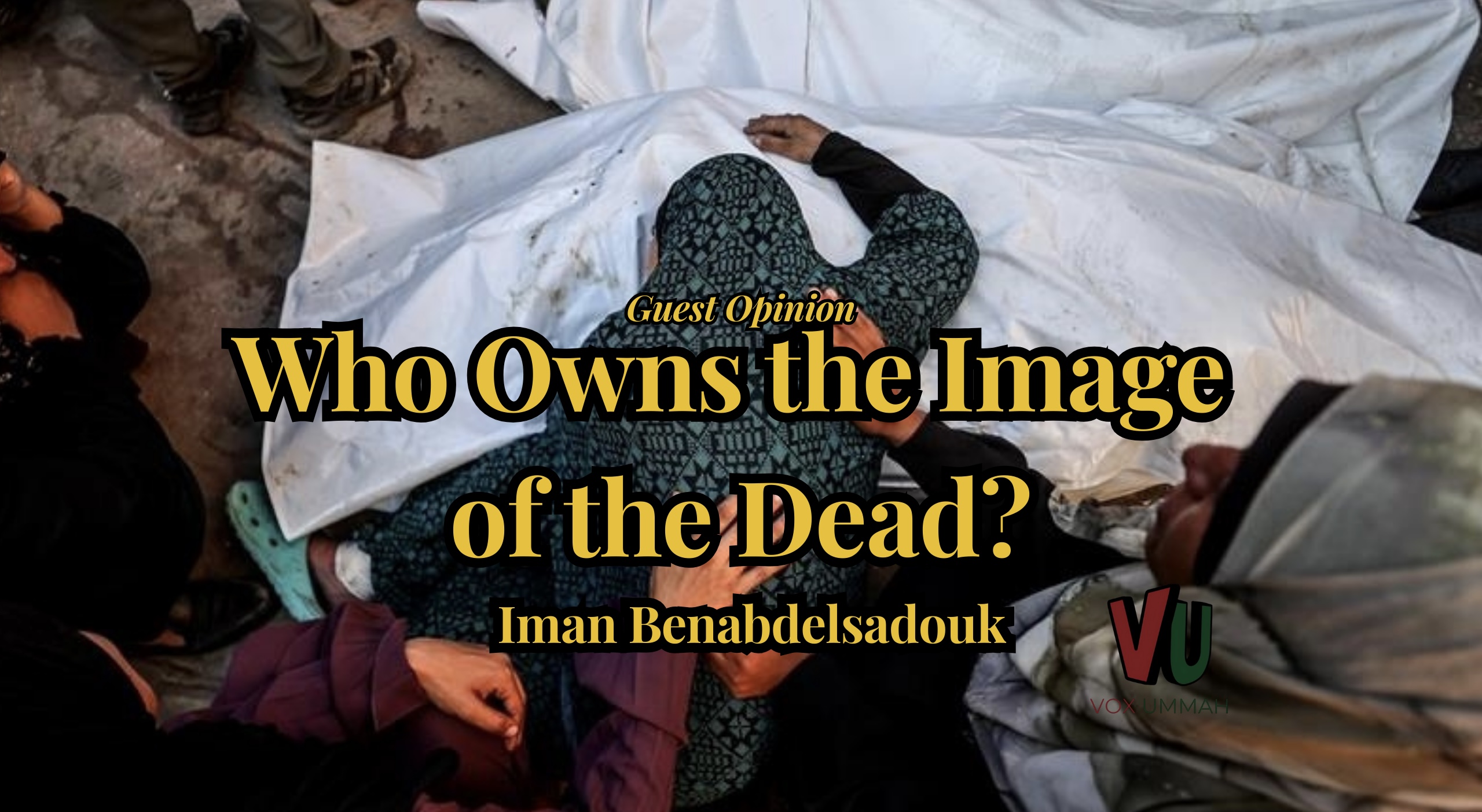

Scroll today: 13.8 million posts on Instagram share the hashtag “#palestine.” These images are of AI, infographics, demolished streets, and dead Palestinian bodies. As the fifth wave of genocide has engulfed the people of Gaza, social media feeds have turned into graveyards filled with brittle bones, organs spilling, and babies half-developed out of their mothers’ wombs. I don’t have to show you these images; you have already seen them. Or maybe I do, because we don’t flinch anymore. We have become desensitized to Palestinian bodies. These were journalists, poets, imams, fathers, students, and children. When did they become just a photo?

Death sells. Walk into any movie theatre and you will find posters on action films detailing blood, gore, and cities collapsing into flames. The spectacle of destruction is entertainment. The same formula runs through mainstream news channels of disaster after disaster; wars, earthquakes, shootings, and crimes (all for your consumption). And this is where the colonial narrative is needed. Images of death are “good news” for social media algorithms. They travel fast, they gather likes and shares. But commodifying grief serves the platform more than the people. Emotional shock eventually fades into emotional numbness, and emotional numbness is the colonizer’s weapon.

Hours after the Israeli regime murdered Anas Al-Sharif, his body was everywhere but laid to rest. Posted, shared, consumed, and scrolled away from. Anas Al-Sharif left us with his will. A testament of defiance: he gave “every effort and all [his] strength to be a support and a voice” for his people, entrusting us with Palestine itself, with his children, with his own family.

He asked not to be reduced to a corpse, but to let his blood be “a light that illuminates the path of freedom.”. Hours after his death, his body was broadcast across social media, even by those who claimed to honor him. Instead of amplifying what he spent his life creating, the narrative became centered on his corpse. Anas himself warned: Israel sought to kill him and to silence his voice. And yet, by ignoring his final words, even his allies carried out that silencing for them. His agency in death was denied. The question becomes inescapable: who owns the image of the dead? The person themselves? Their family? The movement? Or the masses online, driven by the dopamine rush of engagement metrics?

Images of the dead do have a place: in archives, in museums, in courtrooms, and in the history books of a liberated Palestine. They will stand as the record of genocide, a ledger of crimes committed. However, their constant circulation in the midst of the struggle risks draining energy, fracturing their dignity, and aiding the colonizer’s propaganda machine. Right now, our role is to strengthen the living and keep the movement moving. When Palestine is free, we will look back on those images with the full weight of remembrance. In this moment, they can just as easily weaken as they can awaken.

Grief must lead back to action, to prayer, to perseverance. Endlessly circulating images of death trap people in cycles of shock and despair. Islam elevates the martyrs beyond the image of the corpse. To show their bodies again and again is to flatten what Allah has raised, reducing eternal honor to a moment of gore. The Prophet ﷺ reminded us that despair is a form of defeat, and colonial powers thrive on it as a form of psychological warfare. In our ethics, advocacy must avoid tools that drain the ummah’s morale. Instead, we look to his example: even at Uhud, surrounded by martyrs, he led the community back to prayer, unity, and preparation for what was to come next.

We must choose to share differently. Lives before loss; names, stories, dreams, the moments of joy and pride that define a person more than their final breath. Survivor testimonies, cultural resilience, symbols of resistance, verified evidence, and calls to action. To honor the dead is to protect their images from becoming tools for the oppressor or fodder for fleeting outrage. The most powerful picture we can show the world is not just the body in the street, but the people who, despite everything, refuse to disappear and resist forward.

The camera bore witness. The world can no longer claim to be blind. History will not remember that you saw it—it will remember what you did.

Iman Benabdelsadouk is an Algerian Muslim writer that explores stories of faith, struggle, and liberation