Minelle Ali

A day before Iranian President Massoud Pezeshkian’s official state visit to Pakistan, Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi penned an article titled “A Shared Future” in the Pakistani newspaper The Nation. A foreign minister of one country writing an article for another’s isn’t just a casual op-ed – it’s a deliberate, high-visibility diplomatic gesture, geared not only at engaging the leadership but also at influencing public sentiment and fostering grassroots support for deeper bilateral relations. In the article, Araghchi emphasized that the 900-kilometre border Iran and Pakistan share is more than just a line on a map; it’s a historic bridge linking peoples and civilizations for centuries.

The border, which runs between Pakistan’s Balochistan and Iran’s Sistan-Baluchestan, winds through some of the most challenging terrain in the region. Flat desert stretches fade into jagged mountains, with broad, empty plateaus spanning in between. It’s a landscape that resists control – remote, dry, and unforgiving. Official crossings are few; Taftan on the Pakistani side and Mirjaveh on the Iranian side handle most of the legal movement of goods and people. Most of Balochistan, however, is not under consistent and official government patrol. For decades, Baloch separatist groups have taken advantage of the border’s vast, unguarded stretches, slipping back and forth to strike security forces before disappearing into the terrain they know so well.

Both Pakistan and Iran have long understood the fragility of this shared border, but for the rest of the world, it came into sharp focus in January 2024. On 16 January, Iran launched missile and drone strikes into Pakistan’s Balochistan province, hitting positions of the Sunni militant group Jaish al-Adl. Two days later, on 18 January, Pakistan responded with precision air strikes on hideouts of the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) and Balochistan Liberation Front (BLF) in Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan province.

A Crisis Contained, A Partnership Reaffirmed

What could have spiraled into a very prolonged confrontation was almost immediately defused. Just four days later, Iran announced that its Foreign Minister, Hossein Amir-Abdollahian, would be visiting Pakistan soon to rebuild ties. We saw how, within days, top-level communication was entirely restored and ambassadors returned to their posts. In Islamabad, it was clear the strikes were not aimed at Pakistan itself but formed part of a calculated display of force – in mid-January 2024, Iran’s IRGC launched a tightly coordinated, 48-hour campaign targeting not only militant hideouts inside Pakistan, but also what it saw as existential, Mossad-linked threats in Erbil, Iraq and ISIS positions in Syria’s Deir ez-Zor province.

The speed of reconciliation underscored a harsh reality: neither Iran nor Pakistan could afford a prolonged confrontation when genuine strategic cooperation was urgently needed. By June 2024, this renewed engagement took on a sharper edge as, at the close of his visit to Islamabad, Abbas Araghchi made an unusually pointed remark, telling reporters that both Iran and Pakistan believed there were clear links between Balochistan-based militants and Israel. The claim was striking because Iran has long accused Israel of stirring unrest in its Sistan and Baluchestan province, but this may have been the first time it suggested Pakistan shared that view. Islamabad has never officially blamed Israel for terrorism in Balochistan, yet during the 12-day Iran–Israel war, it was conspicuously vocal in condemning Israeli – and even American aggression against Tehran.

Against this geopolitical backdrop, President Masoud Pezeshkian made his first trip to Pakistan. The visit saw the two countries sign a raft of agreements, ranging from plans to boost bilateral trade to $10 billion, to fresh commitments on combating terrorism and working toward regional peace. Standing beside Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif, Pezeshkian expressed gratitude to Pakistan’s government and people for standing with Iran “during the 12-day terrorist aggression by the Zionist regime and the United States.” Sharif responded in kind, voicing Pakistan’s backing for Iran’s right to pursue a peaceful nuclear program under the UN charter, and condemning Israel’s war on Iran, saying there was “no justification” for it.

The Regional Connectivity Chessboard

We know, of course, that security ties and economic imperatives are not separate domains; they reinforce one another in a mutually sustaining loop. The U.S. and Israeli strikes on Iran in 2025 drove home this lesson for many regional states as the shockwaves didn’t stop at Tehran – they rippled across Central Asia, shaking its reliance on Iranian ports and overland routes as vital lifelines to global markets. Some observers have pointed out that Iran’s newly launched rail link to China, which would help Iran evade sanctions, was one of the reasons behind Israel’s strikes on Iran. In its wake, governments are now scrambling to rethink their trade strategies. Uzbekistan, for example, is now considering an expensive pivot to shift freight away from Iran, a move that could push logistics costs up by as much as 30% while placing bets on the Trans-Afghan Railway, a planned line connecting Termez to Pakistan’s Arabian Sea ports:

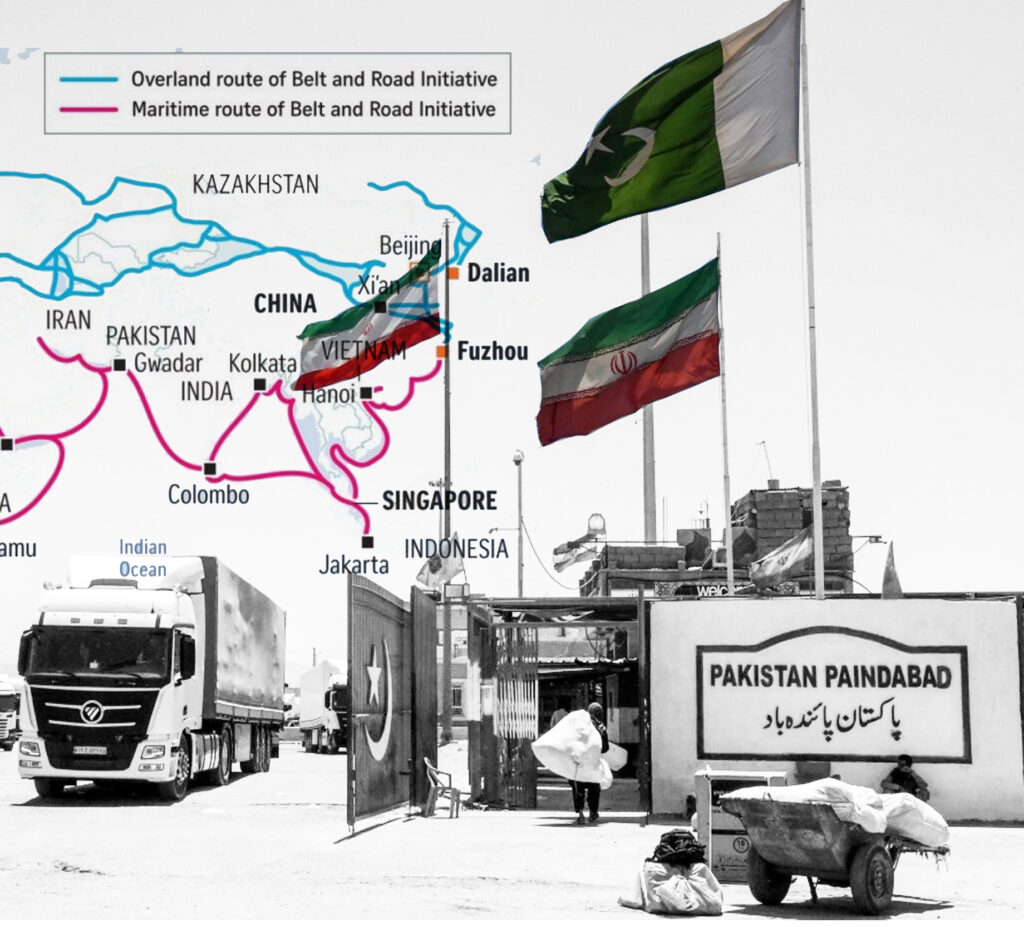

The imperialist goal is to undermine regional connectivity and erect new obstacles to Eurasian integration. Iran doesn’t view these changes in regional trade routes as peripheral concerns, as they directly impact its long-term economic objectives. Suppose Central Asian freight begins to bypass Iranian territory. In that case, Iran risks losing not just significant transit revenue, but also its position as a key link between Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. In this context, Pakistan’s role as a transit hub becomes crucial. By connecting to Pakistan’s transport networks, especially those linked to CPEC, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, and the proposed Trans-Afghan Railway, Iran can maintain its role in regional supply chains, even as some partners explore other routes and corridors.

Iran is already moving quickly to protect this role as a regional transit hub. It’s rolling out three new international rail links to Turkey, Afghanistan, and Turkmenistan, while working with Pakistan and Turkey to restart the Istanbul–Tehran–Islamabad (ITI) freight corridor under the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO). For Pakistan, this means pursuing two complementary tracks: Chinese-financed trade routes as well as Iran-inclusive corridors that offer an alternative to Western-backed networks. The Russian-led International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) is also central to this vision, as it is designed to connect India, Iran, Russia, and Central Asia via a shorter and cheaper alternative to traditional maritime routes. In 2024, Pakistan also became an official member state of the INSTC. But this is about more than just trade -it’s about building overall resilience. Both nations can strengthen their resistance to future geopolitical shocks by combining Chinese and Russian investment with possible Gulf funding and locally based projects. To realize this goal, their participation as members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) is vital. While the Tehran-based ECO provides commercial agreements, technological standards, and legal frameworks, the China- and Russia-led SCO focuses on security coordination and counterterrorism to ensure these trade corridors operate safely.

Although Chabahar in Iran and Gwadar in Pakistan are often cast as rivals, in a multipolar world, they could work hand in hand. Gwadar, central to CPEC, gives China quick access to the Arabian Sea. Chabahar, although backed by India, offers Afghanistan and Central Asia a route that bypasses Pakistan. However, if politics align, both ports could be linked into a larger network, thereby tying the Belt and Road Initiative to Iran’s trade corridors, the INSTC, and regional frameworks such as the ECO and SCO. This potential is confirmed by the fact that when Pezeshkian visited Pakistan, he stated that Iran is ready to join the Silk Road. Iran has also previously expressed interest in joining CPEC on many occasions.

Pakistan–Iran Border Markets: Gateways to Sovereignty in a Multipolar Eurasia

In today’s emerging multipolar order, the Pakistan–Iran border markets carry far greater weight than their humble appearance suggests. For Iran, they’re one of the few external markets that are functioning despite Western sanctions. For Pakistan, they’re a way to secure energy, maintain steady food supplies, and expand trade, making the country less reliant on distant, conditional Western markets. Much of this trade occurs informally, so while it keeps border communities afloat, it also robs both governments of revenue and erodes the strategic importance of regulated commerce. In April 2021, Islamabad and Tehran sought to change this by agreeing to establish six joint border markets. The first three Gabd, Mand, and Chadgi are designed to channel this “gray” trade into regulated, tax-generating commerce. Beyond reducing smuggling, they aim to revitalize neglected regions and provide residents with viable, legal alternatives to illicit activity.

The true power of these markets lies in their integration into broader regional connectivity networks, which are linked to road, rail, and energy corridors spanning West Asia, Central Asia, and the Indian Ocean. This is precisely why such initiatives face resistance from Western and Israeli strategic circles, because by securing its western flank through economically vibrant corridors connected to Iran and beyond, Pakistan gains strategic depth outside U.S.-aligned routes and alleviates maritime vulnerabilities. In this context, secure border markets are not merely tools of trade policy; they are integral to Pakistan’s national defence architecture.

Where Borders Divide, History and Trade Must Unite:

The challenge these two nations face is striking a balance between robust security measures and ensuring that local communities benefit from the trade boost. Without their support, these markets risk becoming targets instead of sources of stability. What’s at stake couldn’t be clearer. If these regions are ignored, smuggling, unrest, and growing economic dependence will fill the gap. However, if we invest thoughtfully in transforming these corridors and markets into hubs of sustained, legal, and regulated trade, Pakistan could firmly integrate into the Eurasian connectivity network, shield its economy from external pressures, and gain genuine freedom to make its own sovereign choices.

Many Pakistanis and Iranians today may not be aware that long before modern borders existed, camel caravans traversed ancient paths between Balochistan and Sistan, carrying spices, textiles, and ideas across the land. Communities on both sides were deeply connected, sharing the same languages, celebrating the same festivals, and forging ties through marriage, regardless of checkpoints or barriers. These routes were so much more than just trade paths. They were bustling gateways where merchants, artisans, and travelers linked the Persian Gulf and the Indus. Fracturing this connection would be like imposing an alien divide that disregards centuries of shared culture and history.

Minelle Ali is a Pakistani architect, writer, and founder of South Shaheen, a blog exploring the intersection of infrastructure and geopolitics. Her architectural background shapes her analysis of the Belt and Road Initiative and regional trade corridors, viewing them as both geopolitical strategies and physical infrastructures transforming communities.